Languages and Ethnic Groups of Bhutan

An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

As the Language Gulper has no advertisements it is essential that we receive some financial help, however small, in order to keep the site running and eventually expand it.

So, please, make a donation if you can.

Overview. Bhutan is a landlocked country between China and India. It shares borders in the north with the Tibetan Plateau, in the west with mountainous Sikkim and Darjeeling, in the south with the Bengal-Assam plains, and in the east with the highlands of Arunachal Pradesh. Its main cities are: the capital Thimphu (100,000 inhabitants), Phuntsholing (25,000), and Gelephu (10,000); Paro has the only international airport; Punakha was the capital until 1955.

The country may be divided into three broad physical regions: the high valleys of the Great Himalayas in the north, cold and inhospitable, the mild valleys of the Lesser Himalayas in the centre, and the humid and densely forested Duars Plain in the south. Of these three regions, the Lesser Himalayas are the most favorable for human settlement harboring most of Bhutan's population.

The early history of Bhutan is obscure until four or five hundred years ago when a lama from Tibet became the religious and political leader of the region. He exercised both spiritual and temporal power but, later, the two spheres were in charge of separate individuals. In spite of several invasions by the Chinese and the British, Bhutan managed to remain independent by following an isolationist policy. Most of Bhutan's population are Tibetan Buddhists, belonging to the Nyingma or Kagyu schools, two of its four main orders.

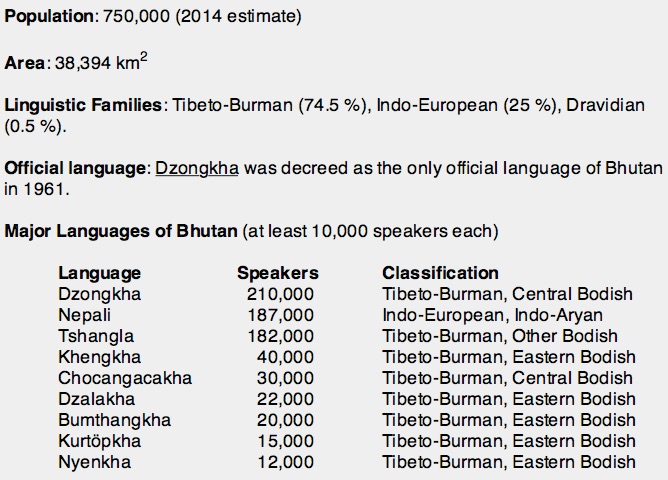

The first and last census of Bhutan was completed in 2005. The population in 2014 is estimated to be around 750.000 people, inhabiting an area of 38,394 square kilometers. Some 22 living languages belonging to three unrelated families, Tibeto-Burman, Indo-European and Dravidian, are spoken in its territory. The major languages of Bhutan are Dzongkha, Nepali and Tshangla.

A list of Bhutan languages with at least 10,000 native speakers is shown in the following table:

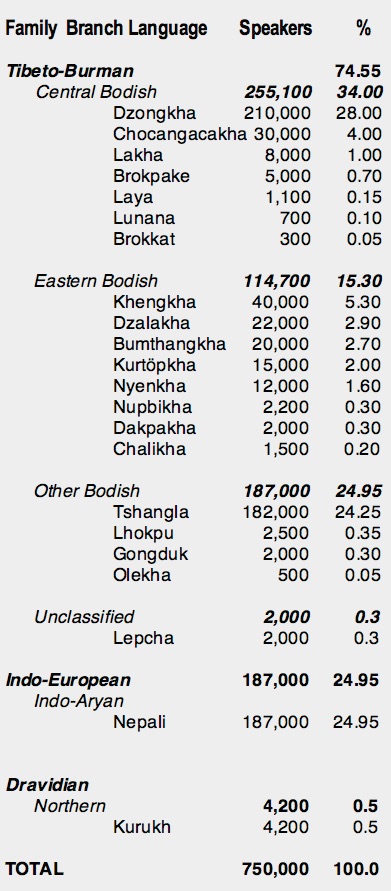

The only Indo-European language spoken in Bhutan is Nepali which belongs to the Indo-Aryan branch. The Dravidian family, native of India, is represented only by Kurukh.

A complete list of Bhutan living languages ordered by linguistic families and number of speakers is the following:

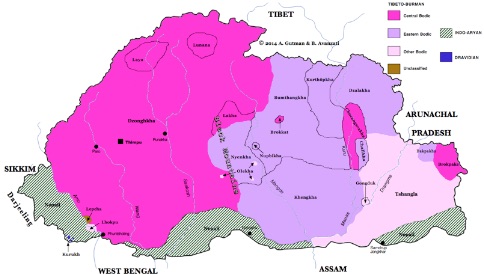

Language Distribution

Central Bodish languages predominate in the west of Bhutan. Dzongkha ("the language of the fortress") is the most widely spoken of this group and the official language of the country; it is the majority language in eight out of the nine westernmost districts (Gasa, Punakha, Wangdue Phodrang, Dagana, Thimphu, Paro, Chukha and Haa). Dzongkha is the only language of Bhutan with a literary tradition. It is used as a lingua franca in the west while Tshangla is the lingua franca of the east and Nepali plays the same role in the south. Laya and Lunana, spoken in the northwest of Bhutan by yak herders, are considered dialects of Dzongkha by most scholars.

Lakha is spoken to the east of Dzongkha, north of the Black Mountains, a vertical range that separates west and central Bhutan. Brokkat is spoken in the village of Dur in central Bhumtang district. Chocangacakha is spoken in the east, along the valley of the river Kuru, and Brokpake is spoken further to the east, in Mera and Sakteng, close to the border with the Indian province of Arunachal Pradesh.

East Bodish languages, with the exception of Dakpakha, are spoken in the central part of Bhutan. Bumthangkha, Khengkha, and Kurtöpkha are a cluster of closely related languages. A second cluster includes Nyenkha, Nupbikha, and Chalikha. Dzalakha and Dakpakha form another cluster; the former is spoken mainly in Bhutan, but also in a neighboring area of Tibet (mTsho-sna county), the latter is spoken in a few villages of eastern Bhutan as well as across the border in the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh (Tawang district).

Other Bodish languages of Bhutan don't fit easily in any particular Bodic group. Tshangla, by far the most numerous, is spoken in east and southeast Bhutan as a primary language but also as a lingua franca. It is also spoken outside of Bhutan in portions of Tibet and Arunachal Pradesh. Lhokpu is spoken in the southwest of the country, in five villages of Samtse district. Gongduk is found in a small area of the Mongar district, in south-central Bhutan. Olekha is spoken in several villages across the Black Mountains.

Lepcha's classification is not settled yet. In Bhutan it is confined to a few villages in the Samtse district, in the southwest of the country, close to Sikkim and Darjeeling district in northern India where most Lepchas live.

Kurukh, a Dravidian language, is spoken in the same district as Lepcha, close to the southwestern frontier of Bhutan. Across the border, in West Bengal and in other North Indian states, is where the vast majority of Kurukh speakers are found (more than two million).

Nepali is an Indo-European language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch. It predominates in most areas of southern Bhutan, particularly in the south-west and south-center.

Ethnic groups of Bhutan

a) Ngalop

The Ngalop or "earliest risen" are the descendants of Tibetan immigrants who began arriving into Bhutan about a millennium ago. They predominate in northern, central, and western Bhutan. They speak mainly Dzongkha but also other Central and Eastern Bodish languages, and practice Tibetan Buddhism. Initially, Tibetan lamas and their descendants governed the country from fort-like monasteries with the help of lay officials, who gradually took control of all the political offices. Since the beginning of the 20th century a hereditary monarchy was established. Nowadays, the Ngalop still dominate the political and religious life of Bhutan.

b) Sharchop

The Sharchop or "eastern people" live in eastern Bhutan and speak Tshangla. They exhibit some cultural traits that link them with the peoples of Southeast Asia; they probably migrated a long time ago (before the arrival of the Ngalop) from Myanmar or Assam. They have traditionally practiced slash and burn agriculture clearing a section of forest by burning, and planting rice for a few years until the soil is exhausted. The Government has been trying to discourage this sort of cultivation since 1969. Most Sharchop inhabit dispersed settlements along the mountain slopes where they build houses on stilts. Larger settlements may group around a fortress-like monastery.

c) Ancient Tribal Populations

The Lhokpu, Mönpa, and Gongduk are small, isolated, aboriginal communities that settled in Bhutan from time immemorial. Even if their languages are Bodic, they don't fit in any Bodic group.

The Lhokpu are indigenous to the forested hills of southwestern Bhutan. In contrast to most Bhutanese, they have not adopted Buddhism. Instead, they worship nature gods of the sky, mountains and rivers. They bury their dead in cylindrical stone sepulchers above ground, and don't believe in reincarnation but in a hereafter called Simpu. The Lhokpu have highly endogamous marriage practices of the matrilocal type (i.e., the married couple resides with the wife's parents).

The Mönpa, who speak Olekha, are the remnant of a primordial population of the Black Mountains. They are nominally Buddhists, but their actual religion is Bon (the original religion of Tibet), coupled with animist practices.

The Gongduk language is spoken by a dwindling population in a remote enclave in east-central Bhutan. The Gongduk-speaking people tell that they descend from an ancient lineage and that their ancestors were semi-nomadic hunters. They believe in Tibetan Buddhism mixed with animistic worship of spirits. They practice matrilocal residence like the Lhokpu.

d) Lepchas

The Lepchas call themselves Róng or Róngkup ‘children of the Róng’. The term Lepcha, derived from Nepali, was originally derogatory meaning ‘inarticulate speech’. Nowadays, this ethnonym is widely used without negative connotation. The Lepchas are native of neighboring Sikkim (now a part of India), from which they have migrated to south-western Bhutan and other regions of northern South Asia. Many Lepchas are Buddhists but some are Christian, Hindus, or still practice their ancient Shamanistic religion called Mun.

e) Nepalese or Lhotsampa

The Nepalese are the most recent arrivals in Bhutan. They are called Lhotsampa or "people of the south". They began immigrating into the country in the first half of the 19th century settling in the southern temperate lowlands that are quite suitable for agriculture. The growing numbers of Nepalese prompted the Bhutanese government to ban their further immigration and to prohibit Nepalese settlement in central Bhutan. Through the late 1980s and 1990s, as many as 100,000 fled Bhutan for Nepal when the Government implemented a campaign of "one country, one people" trying to impose uniformity of religion, language and dress. However, most Lhotsampa have kept their cultural identity and language and, thus, the vast majority of them speak Nepali. Most are Hindus though some are Buddhists or Christian.

f) Oraon or Kurukh

The small Oraon community of Bhutan is an extension of much larger populations of northern India. They speak Kurukh, a language belonging to the Dravidian family which is native to India. The traditional religion of the Oraon mixes animist beliefs, the worship of ancestors and Hinduism. A number of Oraon has become Christians.

-

© 2014 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

-

Further Reading

-

-The Sino-Tibetan Languages. G. Thurgood & Randy J. LaPolla (eds). Routledge (2003).

-

-Languages of the Himalayas (2 vols). George van Driem. Brill (2001).

-

-‘Language Policy in Bhutan’. George van Driem. In Bhutan: Aspects of Culture and Development, 87-105. M. Aris & M. Hutt (eds). Kiscadale (1994). Available online at:

-

http://himalayanlanguages.org/files/driem/pdfs/1994LanguagePolicy.pdf

-

-‘The Church State of Bhutan’. Pedro Carrasco. In Land and Polity in Tibet, 194-206. University of Washington Press (1959).

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania