An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Alternative Name: Finno-Ugric. This denomination should be reserved for one of the subfamilies of Uralic and not applied to the entire family.

Overview. Uralic is a very ancient language family prevalent in a vast area of northeastern Europe and northern Asia. Its ancestor, Proto-Uralic, was spoken 7,000 to 10,000 years ago in the vicinity of the Ural Mountains from where the precursors of the Samoyeds disseminated into Siberia, and the Finno-Ugrians into northern Europe and Hungary.

The Uralic languages are typologically very diverse as a result of their antiquity, of the relative exiguity and dispersion of their speakers in very extensive territories, and last, but not least, due to their prolonged contacts with Altaic-speaking peoples to the east and Indo-Europeans to the west. Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian are the largest Uralic languages.

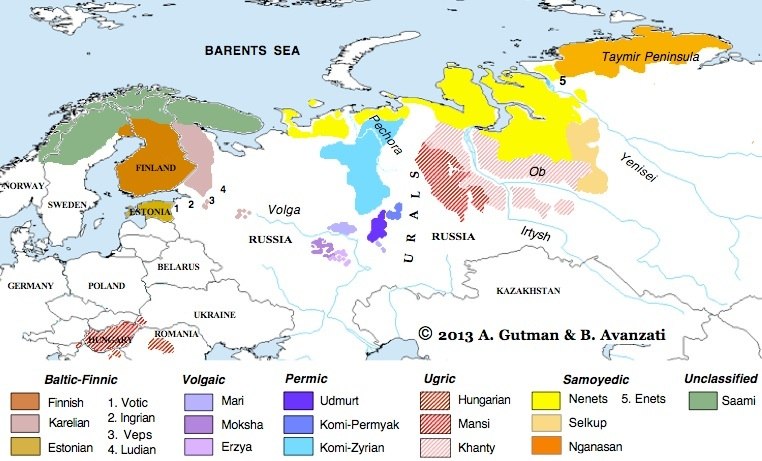

Distribution. Northern Russia, Finland, Estonia, Hungary. Also some speakers in north Norway and north Sweden. Samoyedic languages are spoken in west Siberia.

-

Map of Uralic language branches (click to enlarge it)

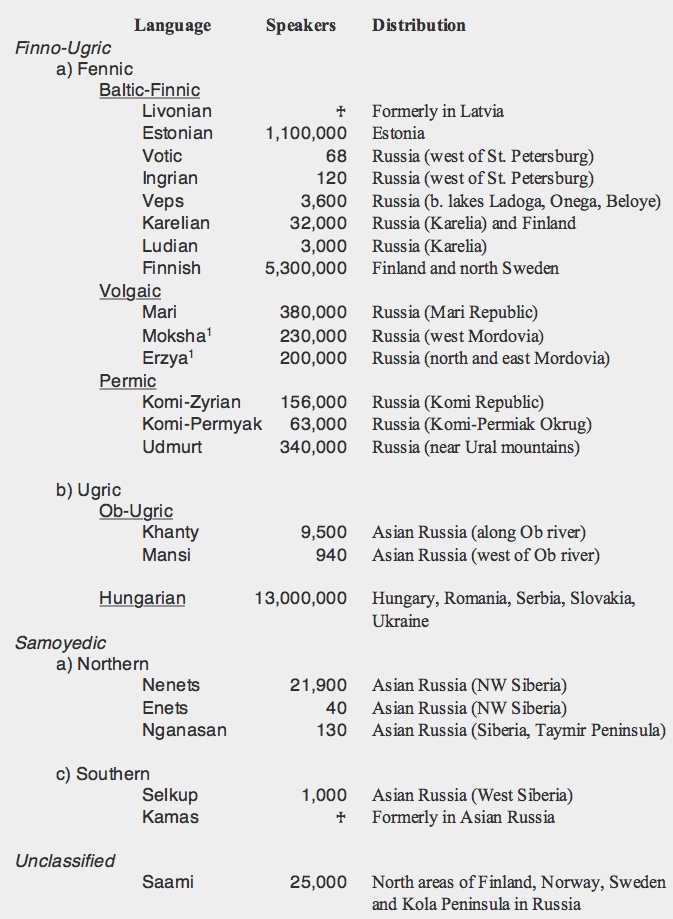

Classification. Uralic is divided in two subfamilies: Finno-Ugric and the much smaller Samoyedic, plus one unclassified language (Saami). Finno-Ugric is itself divided in two, Fennic and Ugric, the first one spoken in Estonia, Scandinavia and European Russia, the second spoken in two widely separated areas: Ob-Ugric languages scattered along the Ob and lower-Irtysh rivers, and Hungarian in Eastern Europe.

1. Moksha and Erzya are known jointly as Mordvin.

Speakers. Uralic languages are spoken by close to 21 million speakers of which about 2 million in Russia. The most widely spoken are (in millions):

Hungarian

Finnish

Estonian

Mari

Udmurt

Moksha

Erzya

Komi-Zyrian

13.00

5.30

1.10

0.38

0.34

0.23

0.20

0.15

Status. Finnish, Estonian and Hungarian are the national languages of Finland, Estonia and Hungary. Notwithstanding that several minority languages of the Russian Federation are granted an official status in their national administrative regions, the number of their speakers is decreasing and some of them are endangered while others are already extinct.

Oldest Documents. The earliest Uralic documents date back to the 13th century in the form of a Hungarian funeral oration and a very brief Karelian fragment. Next, we found Christian texts in Old Permic (the ancestor of the Komi languages) from the 14th century. Printed works, dating from the 16th century, are the first attestations of Finnish and Estonian. Saami was first written in the 17th century.

SHARED FEATURES

-

✦ Phonology

-

-Syllable Structure: Proto-Uralic had, probably, a CVCC syllable structure. Many Balto-Finnic languages have a simpler one avoiding final consonants in syllables that are in the middle or at the end of a word. Exceptionally, Erzya and Moksha allow syllables with initial consonant clusters.

-

-Vowels: Most languages present some sort of quantitative vowel opposition between short and long or between full and reduced. The latter have a very short duration and indistinct quality similar to that of the schwa.

-

-Vowel harmony occurs in Finnish, Hungarian and in various degrees in Volgaic, Ob-Ugric and Samoyedic. In contrast, Estonian does not have it. The opposition is usually between front and back vowels, and sometimes between rounded and unrounded vowels. In compound words, vowel harmony doesn't occur.

-

-Consonants: Finnish has a relatively small inventory of consonants due to the loss of some that were present in the ancestral language. In Proto-Uralic all the stops were voiceless but Hungarian (as well as other languages) has acquired a distinction between voiceless and voiced stops and fricatives, and as a consequence its consonant inventory is much larger than that of Finnish.

-

-Consonant gradation between open and closed syllables is found in Balto-Finnic (Finnish and Volgaic) and Saami. It consists in the 'weakening' of a consonant when it occurs at the beginning of a closed syllable in the following manner:

-

open syllable closed syllable

-

geminate voiceless stop → single voiceless stop

-

single voiceless stop → voiced stop or fricative or zero

-

-Stress falls in many Uralic languages, like in Finnish, Hungarian and Estonian, always on the first syllable. In contrast, in Udmurt it falls on the last one. In some languages stress is not fixed and varies according to vowel quality, morae, etc.

-

✦ Morphology

-

Nominal

-

-Nominal morphology is partly fusional, partly agglutinative. Ob-Ugric is mostly agglutinative. Case, number and possession are marked by suffixes. The number of cases varies from two in Northern Khanty (for direction and location) to 24 in Komi-Zyrian. Saami has 6 cases, Finnish 14, Hungarian 16 to 21. Most languages include nominative, accusative, genitive and three spatial cases for location at, motion towards, and motion from.

-

-The majority of languages distinguish singular and plural numbers. Besides singular and plural, Ob-Ugric, Samoyedic and Saami have a dual number.

-

-Uralic languages make no gender distinction and have no articles except Hungarian and Mordvin. In Hungarian the article precedes the noun and is separable from it, in Mordvin is an inseparable suffix.

-

Verbal

-

-In Proto-Uralic the sole tense distinction was between past and non-past (unmarked). Some modern Uralic languages have several different tenses, which are innovations, and most have indicative, imperative, and conditional moods.

-

-In Proto-Uralic negative sentences were expressed by an auxiliary verb of negation, regularly inflected, followed by the main verb. This is still the case in Finnic and Samoyedic though in Ugric invariable negative particles are used.

-

-Separate subjective and objective conjugations are common in Ugric and Samoyedic; it is also found in Volgaic. In the subjective conjugation a suffix indicates that the focus of the clause is the subject, in the objective conjugation another suffix highlights a specific object within the verbal complex.

-

✦ Syntax

-

-Word order is variable. Some languages are Subject-Object-Verb (SOV), others are Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) and others are quite free. It is mainly an areal feature because in eastern languages the basic word order is SOV, like in neighboring Turkic languages, while in western ones SVO is the rule, like in European languages. Thus, Udmurt, Ob-Ugric, and Samoyed are SOV while Saami, Finnish, Estonian, Komi, and Hungarian are SVO. Modifiers, including genitives, precede their heads.

-

-Besides word order, syntactical relations are indicated by a combination of case marking and postpositions. Postpositions are found in all languages and some do not have any prepositions. In Balto-Finnic languages, however, there are several prepositions in addition to postpositions.

-

-In the protolanguage there was no agreement between adjectives and their heads but now is fairly commonplace, particularly in Balto-Finnic, Samoyedic and Saami.

-

-Coordination and subordination of the elements of the sentence are marked by a variety of means like infinitive verbs, participles, and gerunds. Conjunctions did not exist in Proto-Uralic but modern languages have borrowed them from Germanic and Russian.

Lexicon

Quite surprisingly, Finno-Ugric languages, besides their Uralic core, have a very ancient layer of Indoiranian loanwords. Hungarian has borrowed also form Turkic and Germanic; Permic and Volgaic from West Turkic; Samoyedic and Ob-Ugric from East Turkic, Baltic-Finnic and Saami from Baltic languages. More recently, Slavic has contributed with many words to all of the languages of the family.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-The Uralic Languages. D. Abondolo. Routledge (1998).

-

-'Uralic Languages'. In The Languages of the Soviet Union, 92-142. B. Comrie. Cambridge University Press (1981).

-

-'Uralic Languages'. R. Austerlitz. In The World's Major Languages, 477-483. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-'Common Phonetic and Grammatical Features of the Uralic Languages and Other Languages in Northern Eurasia'. P. Klesment, A. Künnap, S-E Soosaar & R. Taagepera. In The Journal of Indo-European Studies 31(3-4), 1-27 (2003).

-

-A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony, 1581-1990. J. Forsyth. Cambridge University Press (1992).

Uralic Languages

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania