An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Overview. Regarding the number of its speakers, Indo-European is the largest linguistic family today. Its name suggests that some of its members are Asiatic and some European. In fact, the Indo-European family includes the vast majority of European languages and some Asiatic ones. In the last centuries, they have spread to the five continents and are now spoken by half of the population of the planet.

They all derive from a hypothetical precursor called Proto-Indo-European, or simply Indo-European, spoken some six or seven thousand years ago somewhere in Asia. The Indo-European homeland is a matter of controversy because of the difficulty to correlate archeological with ethnic and linguistic data, though several scholars think it was located close to the Caspian Sea. Others believe it was in Anatolia (today's Turkey).

Analysis of vocabulary shared by members of the family suggests that Indo-Europeans were, originally, cattle-breeders living in open villages or in small fortified settlements; they had domesticated sheep, pigs, horses and dogs, they were familiar with metals, their society was patrilineal and male-dominated, their gods were the sky, the sun, the waters, and divine twins associated with horses.

Distribution. Indo-European languages predominate in the whole of the American and European continents with the sole exceptions of Finland, Estonia and Hungary (where Uralic languages are spoken). In Asia, they are in the majority in all South Asian countries (except Bhutan), in Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Asiatic Russia. They are also dominant in Australia and New Zealand while in Africa they are spoken as a mother tongue in few places (Spanish in Equatorial Guinea, Afrikaans in South Africa).

Classification. There are more than 100 languages in the family and they show different degrees of relatedness that allows them to be classified in a dozen European and Asiatic branches:

-

a)Asiatic

-

•Anatolian: all of its members are extinct now but in former times were spoken in the Anatolian peninsula (modern Turkey). They included Hittite, Luvian and Palaic, and their descendants Lycian, Lydian and Carian.

-

•Armenian: is represented only by Armenian.

-

•Iranian: includes Modern Persian, Kurdish, Pashto, Baluchi and several extinct languages of Iran and Central Asia.

-

Map of Indo-European languages (enlarge it)

-

•Indo-Aryan: the many languages of South Asia including Sanskrit and its modern descendants like Hindi, Bengali, Punjabi, Gujarati, Marathi and others.

-

•Tocharian: comprises only two languages, Tocharian A and Tocharian B, both extinct, recorded in Buddhist documents unearthed in some city-oases of the Silk Road in Xinjiang, China.

-

b) European

-

•Germanic: German, Yiddish, English, Dutch, Frisian and the Scandinavian languages Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Icelandic, and Faroese.

-

•Italic: Latin and its descendants, including Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, Provençal, French, Italian and Romanian.

-

•Baltic: Latvian and Lithuanian, besides the extinct Prussian.

-

•Celtic: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Welsh and Breton as well as several extinct continental tongues.

-

•Hellenic: Greek, ancient and modern.

-

•Albanian: represented only by the Albanian language.

Major Languages and Speakers

Indo-European languages are spoken by more than 3 billion people. The largest among them are (in millions of native speakers):

SHARED FEATURES

-

✦ Phonology

-

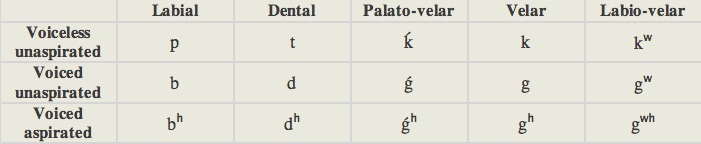

-Consonants. Reconstruction of the phonology of Proto-Indo-European is difficult due to the many changes that the languages of the family have experienced and because of the frequent impossibility of distinguishing between archaisms and innovations.

-

The most important topic concerns the reconstruction of the stops (consonants produced by a brief interruption of the airflow). Various models leaned too much on Sanskrit which is the only ancient language of the family that makes a four-way distinction between voiceless and voiced stops, both aspirated and unaspirated. More recent models exclude the voiceless aspirated stops from Proto-Indo-European. These three classes of stops were articulated at five different points in the oral cavity:

-

Besides the stops, there were the fricative s (produced by air-friction), three laryngeals (h1, h2, h3), two nasals (m, n), two liquids (r, l) and two semi-vowels (y, w).

-

The palato-velars evolved differently in the Centum and Satem languages, names based on the word for the number one-hundred in Latin and Avestan, respectively. In the Centum languages the palato-velars fused with the velars, the word hundred being pronounced, thus, kentum (written centum) in Latin, (he)katon in Greek, känt in Tocharian A, ket (written cet) in Old Irish and hun in Gothic (derived from kun). In contrast, in the Satem languages the palato-velars became the fricative s giving satem in Avestan and sad in Persian, śata in Sanskrit, simtas in Lithuanian, sito in Old Slavonic.

-

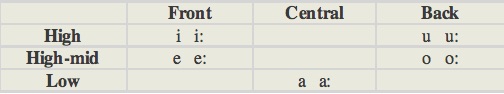

-Vowels. The protolanguage had five vowels, short and long:

-

-Vowel gradation. In the more ancient languages of the family, one mechanism to indicate the relation of a verb or a noun with other words in a sentence consisted in changing the vowel of the root, a process known as vowel gradation or ablaut. Another mechanism, which became predominant, was to add different suffixes to an invariable root, the process we call inflection. Remnants of vowel gradation subsist in the majority of modern Indo-European languages. There are two types of vowel gradation: quantitative and qualitative. The first one consists in the strengthening or weakening of a basic vowel. For example, e changes into strong ai or it is reduced to weak i. The second one implies a change in the quality or “color” of a vowel. For example, e changes into o or is elided.

-

-Accent. Apparently, in Proto-Indo-European there was a musical accent in which a rise in pitch (sound frequency) highlighted a syllable of the word. This kind of accent served to mark grammatical functions. Solely Vedic Sanskrit and Ancient Greek preserved the pitch accent of Proto-Indo-European while in other languages it was replaced by stress accent which highlights a syllable by pronouncing it louder and longer.

-

✦ Morphology

-

Nominal

-

-Indo-European languages exhibit a great morphological diversity at the nominal and verbal levels. The more ancient languages within each branch were inflective, employing suffixes added to the root to mark not only gender and number of nouns, adjectives and pronouns but also their syntactical relations.

-

-Thus, Proto-Indo-European had eight cases: nominative, vocative, accusative, instrumental, dative, ablative, genitive and locative, distinguishing three numbers (singular, dual, plural) and three genders (masculine, neuter, feminine). None of the languages of the family, with the single exception of Sanskrit, preserves this complex system, though Old Church Slavonic and Ancient Armenian had seven cases, Latin had six, Ancient Greek five and Hittite four. Several modern Slavic and Baltic languages have six or seven cases, modern Armenian has five and German four.

-

-Adjectives agree with their nouns in case, gender and number being inflected in the same way as nouns. Pronouns are similarly inflected but, frequently, have some suffix markers of their own. In many modern languages the case system has been considerably simplified or has completely collapsed.

-

Verbal

-

-The verbal system was also complex in most ancient languages, and remains so in many modern ones. Besides having diverse tenses, they indicated various moods, aspects and voices.

-

-Thus, four moods were frequently marked: indicative (expressing a fact), optative (suggesting possibility, wish or ability), subjunctive (doubt, probability of occurrence in the future), imperative (command).

-

-Generally, there were two voices: active, and middle (reflexive) or passive. Ancient Greek and Sanskrit, exceptionally, had three voices (active, middle, passive).

-

-More than temporal relations, the Indo-European verb marked aspect. The imperfective aspect denoted an incomplete, continuous or habitual action; the perfective aspect a simple, indefinite, completed action; the perfect aspect a completed action whose results perdure.

-

✦ Syntax

-

-Word order in many ancient Indo-European languages (Hittite, Sanskrit, Latin, Tocharian) was predominantly Subject-Object-Verb (SOV). However, as they were heavily inflected, word order was relatively free since syntactical relations were determined mainly by case. The agent (the performer of the action) adopted the nominative case and the object of the verb the accusative while the other cases marked other grammatical functions like possession (genitive), instrument or company (instrumental), source or cause (ablative), indirect object or purpose (dative), spatial or temporal location (locative).

-

-In modern Indo-European languages word order is quite variable. Some branches, such as Iranian and Indo-Aryan, have retained the SOV order. Other branches (Italic, Germanic, Greek) have switched to a predominantly Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) order. Exceptionally, Celtic languages are strictly VSO.

-

-In ancient SOV languages, genitives and attributive adjectives usually precede their nouns, relative clauses precede main ones, and postpositions are used. In contrast, SVO languages employ mainly prepositions, and adjectives tend to follow their nouns but there are many exceptions (that some scholars interpret as a relic of the ancient order).

-

-The capacity to form compound words provided an additional means of expression, concise and elegant, in which ambiguity played a no minor role since syntactical relations between the members of the compound were not explicit. Most compounds were nominal including nouns and/or adjectives, sometimes pronouns as well. Most compounds had only two words or, at most three, but in Classical Sanskrit longer and frequent compounds became the norm. Several modern languages have retained this compound-forming ability while in others it has been lost.

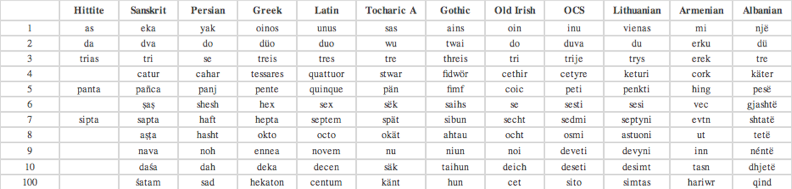

Lexicon

One of the major criteria to determine affiliation between languages is a shared vocabulary. The words for numerals are quite resistant to change and tend to be well preserved as the following table illustrates:

Note: the names of Hittite numerals is largely unknown. OCS refers to Old Church Slavonic

-

click the table to enlarge

The Branches of Indo-European

Anatolian

The most ancient member is Hittite documented in some 25,000 clay tablets engraved with cuneiform characters, discovered by the archaeologists at Bogazkoy (the ancient Hattusa) in present Turkey. They constitute the oldest Indo-European documents so far, dating back to the 17th-13th centuries BCE.

The Hittites were newcomers to the Anatolian Peninsula borrowing part of their culture and vocabulary from their non-Indo-European neighbors as evidenced by loanwords from Hattic and Hurrian. The Hittite language was not as morphologically complex as other coetaneous Indo-European languages, being distinguished by a number of archaic features which suggest an early split form Proto-Indo-European.

Close to Hittite were Luvian, spoken to the west and south of it, and Palaic, prevalent to its northwest. After the fall of the Hittite empire, Hittite and Palaic became extinct but Luvian subsisted giving birth perhaps to Lycian. Other late Anatolian languages were Lydian and Carian which succumbed (with Lycian) to the advance of Greek towards the end of the first millennium BCE.

Armenian

It is represented by just one language, Armenian, spoken in Armenia, Southern Russia, Georgia and Azerbaijan. The first Armenian texts are of a religious nature and quite late, as they do not predate the 5th century CE. However, the first references to the Armenians are much earlier and the name Arminiya is mentioned, already, in 600 BCE. Indigenous to the Balkans, they settled in the area of Lake Van occupying the territories left free after the fall of Urartu, a kingdom created by a non-Indo-European people. When the Armenians converted to Christianity, an alphabet of 36 letters was conceived, attributed to Bishop Mesrop Mashtots who employed it to translate the Bible.

Armenian which exists today in two varieties, Eastern and Western, has been markedly influenced by the languages it came into contact with, like Persian, Greek and Arabian. Quite conservative in its structure, it still has six or seven grammatical cases.

Iranian

The Iranian branch is closely related to Indo-Aryan, so they usually are grouped together as Indo-Iranian. The Iranian languages spread, formerly, all over the Asiatic steppes but later were displaced by Turkic languages, and nowadays they are restricted to Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and parts of Turkey and Pakistan. The most ancient ones are the Old Persian of Achaemenid inscriptions, and the Avestan of the Avesta, the sacred book of Zoroastrianism. The first one, written in cuneiform characters, was native to southwestern Iran while the second originated in the east of the country. The oldest layer of Avestan is found in the hymns of the Gathas, attributed to Zarathustra himself; it had, like Sanskrit, three genders, three numbers and eight cases.

Later, Middle Persian or Pahlavi evolved from Old Persian, Parthian replaced Avestan in the north of Iran, and documents bear witness of the existence of an oriental group of Iranian languages in Central Asia and Afghanistan including Ossetian, Bactrian, Sogdian, Chorasmian, and Khotanese. Finally, the modern Iranian languages, including Modern Persian (Farsi), Kurdish, Balochi, Pashto and others made their appearance.

Indo-Aryan

Sanskrit is not only one of the earliest documented Indo-European languages but also the one with the vastest and most informative ancient corpus. In contrast with Hittite and Mycenaean, in Archaic or Vedic Sanskrit we don't find administrative and economic texts but a religious poetry of the first order. Another difference with those languages is that the Vedic hymns and ritual formulae were passed down orally from one generation to another, in the course of one millennium, until they were written down. Transmission was very faithful since ritual efficacy depended on the exact pronunciation of sounds and words.

Grammatically complex, Sanskrit preserved the eight cases, three genders and three numbers of Proto-Indo-European as well as its ability to form compound words which it even increased until it became one of its most powerful means of expression. Both Archaic (Vedic) and Classical Sanskrit belong to Old Indo-Aryan. Middle Indo-Aryan includes Pali, a vernacular language of northern India that became the vehicle of the Buddhist Canon, and several other popular tongues or Prakrits like Sauraseni, Maharashtri, Magadhi and Ardhamagadhi. The last one served as the vehicle of the Jain Canon.

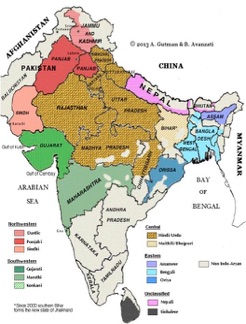

Modern Indo-Aryan comprises an even greater array of languages divided into:

-

Central: Hindi, Urdu, Maithili, Bhojpuri, and Romani (the only Indo-Aryan language based outside South Asia).

-

Oriental: Bengali in West Bengal and Bangladesh, Oriya and Assamese in the Indian states of Orissa and Assam.

-

Northwestern: Punjabi, Sindhi, Lahnda, Pahari, and the Dardic languages (of which Kashmiri is the largest) in Pakistan and India.

-

The classification of Nepali (spoken in Nepal) and Sinhalese (spoken in Sri Lanka) is disputed. The only known relative of the latter is Dhivehi, the main language of the Maldives.

Map of Indo-Aryan languages

-

(click to enlarge it)

Tocharian

Archeological excavations performed at the beginning of the 20th century in some city-oases of the Silk Road revealed religious and commercial documents written in two closely related languages, Tocharian A and Tocharian B, previously unknown. These texts date from the 5th to 10th centuries, those in Tocharian A from Turfan and those in Tocharian B from Kuca (both sites belong nowadays to the region of Xinjiang in western China). Tocharian shows more affinity with European languages of the family than with Asiatic ones, being of Centum type. It has archaic features that suggest it separated early from Proto-Indo-European, probably after Anatolian.

Germanic

Germanic languages are divided into three groups: northern, western and eastern. The first one includes Danish, Norwegian, Swedish and Icelandic. The second one, English, German, Dutch, Afrikaans, and Frisian. The third is extinct, but perdures a Bible in Gothic dating form the 4th century CE, translated by Bishop Ulfilas in an alphabet made up by himself on the base of the Greek and Latin scripts. Even older are runic inscriptions engraved in stone and wood using a special alphabet called Futhark.

The Germanic peoples would have migrated, before 1000 BCE, to south Scandinavia and north Germany where they found non-Indo-European populations who influenced, decisively, the phonology and vocabulary of Proto-Germanic. Thus, it differs from Proto-indo-European in some radical phonetic mutations of which the most important is the 'First Germanic Sound Shift' also known as 'Grimm's Law' that affected all consonant stops:

-

-unaspirated voiced stops became voiceless (b, d, g ⊳ p, t, k):

-

• Russian jabloko ⊳ English apple

-

• Latin decem ⊳ English ten

-

• Latin genu ⊳ English knee

-

-voiceless stops became voiceless fricatives (p, t, k, ⊳ f, θ, x/h):

-

• Latin pedis ⊳ English foot

-

• Latin tres ⊳ English three

-

• Greek kuon ⊳ English hound

-

-aspirated voiced stops became first voiced fricatives and, later, unaspirated voiced stops

-

(bh, dh, gh ⊳ b, d, g):

-

• Sanskrit bhratri ⊳ English brother

-

• Sanskrit madhu ⊳ English mead

-

• Latin hostis ⊳ English guest (from the Indo-European root *ghosti)

On the other hand, Germanic morphology was simplified, as shown by the reduction of cases from eight to four in German due to the disappearance of the vocative and the fusion of the dative, instrumental, ablative and locative in a single case. In other languages of the branch the case system collapsed altogether.

Italic

Italic includes the so-called Romance languages (Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese, Italian, French, Provençal and Romanian) derived from Latin, besides others known only by a few inscriptions and whose filiation is, sometimes, doubtful like Faliscan, Oscan, Umbrian, Picene and Venetic.

From the 6th century BCE, there are abundant inscriptions in Latin followed by literary and rhetorical texts. Latin, originally a language of a small region in the centre of the Italic Peninsula (Latium), disseminated across western and southern Europe as well as through the coastal regions of North Africa coinciding with the expansion of the Roman Empire. Formal Latin coexisted with Vulgar Latin, rarely written, spoken by the people at large (mostly illiterate), from which derive, ultimately, the Romance languages. In the Middle Ages, Latin ceased to be an oral means of communication being employed exclusively for religious and literary purposes.

In Latin the dual number of Proto-Indo-European disappeared though it kept its three genders, and cases were reduced to six (with traces of a seventh) when the ablative, the instrumental and the locative merged.

Baltic

The Baltic branch has similarities with Slavic being, generally, gathered under Balto-Slavic. It also shares some features with Germanic and maybe even with Tocharian. Due in part to the expansion of Slavic, only two Baltic languages have survived: Lithuanian and Latvian (Estonian belongs to the non-Indo-European Uralic family). Other Baltic languages became extinct, first among them Prussian, eclipsed in the 18th century by German. Notwithstanding the late date of the first Baltic texts available, they play, thanks to their conservatism, a key role in the reconstruction of Indo-European language, religion and culture.

Prussian was inflected in five cases while Lithuanian and Latvian, quite distant from Prussian, have seven cases (the ablative was lost) though only two numbers and genders.

Slavic

The Slavic languages share a common ancestor with the Baltic languages having a minor affinity with Indo-Iranian and Armenian (Satem languages). They are divided into eastern, western and southern groups. The first one includes Russian, Belorussian and Ukrainian. The second one, Polish, Czech and Slovak. The third one, Serbo-Croat, Slovenian, Bulgarian and Macedonian.

Old Church Slavonic was the first written Slavic language, employing two closely related alphabets, Glagolitic and Cyrillic, devised for Biblical translations. A more recent form of Slavonic is still used in the liturgy of the Orthodox Church. The divergence of Slavic languages is relatively recent starting between the 10th and 12th centuries.

Slavic languages have prototypically seven out of the eight cases of Proto-Indo-European, the ablative having been lost like in Baltic. In some modern languages, like Bulgarian and Macedonian, the case system has in great measure disappeared; they use prepositions, instead, to establish syntactical relations. In contrast, other Slavic tongues, like those of the eastern and western groups preserve it intact.

Celtic

Celtic languages covered a great part of Europe in the first millennium BCE, but with the advance of the Romans and Christianity they were confined to Britain, Ireland and Brittany. Of the poorly documented continental languages, Gaulish and Hispano-Celtic or Celtiberian are the best known. The first was spoken in vast areas of central and western Europe as well as in the Anatolian Peninsula, the second in the north of the Iberian Peninsula.

Nowadays, only the insular languages survive (though in decline). Attested from the 4th century CE, they are divided into Goidelic and Brythonic groups. The first one encompasses Irish, Scottish Gaelic and the extinct Manx which was spoken in the isle of Manx, the second one includes Welsh, Breton and the extinct Cornish which was spoken in Cornwall. Cumbric and Pictish are two other, poorly documented, insular Celtic languages.

In all Celtic languages a phonetic process known as 'initial consonant mutation' is widespread. It consists in the weakening of certain consonants at the beginning of a word triggered by grammatical markings and the presence of various particles.

Hellenic

Greek in its different stages (Mycenaean, Archaic, Classic, Koine, Byzantine, and Modern) is the sole member of the Hellenic branch. Mycenaean Greek was written for the first time around 1400 BCE in clay tablets, found in Knossos, Crete, with a syllabic system called Linear B, deciphered just a few decades ago. In consequence, Greek is one of the earliest documented languages within Indo-European, along with Hittite and Sanskrit, though its first texts provide scant cultural information due to their bureaucratic and commercial nature. Around 700 BCE, the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet adding to it a notation for vowels which it did not have (like other Semitic writing systems).

Mycenaean had six cases as a result of the fusion of the dative with the locative, and the loss of the ablative. In Archaic Greek the instrumental was absorbed by the dative-locative, and in Byzantine Greek the latter was lost, remaining only nominative, accusative and genitive which are preserved in Modern Greek. In Ancient Greek, besides cases, nominal inflection distinguished three genders (masculine, neuter, feminine) and three numbers (singular, dual and plural) in nouns and adjectives, like Proto-Indo-European, and like Proto-Indo-European the verbal system had four moods (indicative, optative, subjunctive and imperative). In Modern Greek the dual number and the optative have vanished.

Albanian

Though the Albanians were already mentioned by the Greeks, the Albanian language is only documented since the 15th century. Strongly influenced by its neighbors, it constitutes on its own an independent branch within the Indo-European family though it was probably related to some badly known ancient languages of the Balkans like Dacian and Illyrian. Nominal declension distinguishes five cases (nominative, accusative, dative, ablative and genitive) and, exceptionally for an Indo-European language, between definite and indefinite.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-Indo-European Linguistics. An Introduction. J. Clackson. Cambridge University Press (2007).

-

-Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. B. W. Fortson IV. Blackwell (2004).

-

-The Indo-European Languages. P. Ramat & A. Ramat. Routledge (1998).

-

-'Indo-European Languages'. P. Baldi. In The World's Major Languages, 23-50. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-'Indo-European Languages'. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online (2014).

Indo-European Languages

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania

Urgent call for donations. In order to keep the Language Gulper online we need to raise 500 U.S. dollars before the end of the year. As our website has no advertisements it is essential that we receive some financial help, however small, in order to keep the site running and eventually expand it. So, please, make a donation if you can.