An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Manx

Classification: Indo-European, Celtic, Insular Celtic, Q-Celtic, Goidelic.

According to one hypothesis, Celtic languages are divided into P-Celtic and Q-Celtic. P-Celtic links the Brythonic insular languages (Welsh, Cornish, Breton) with continental Gaulish. Q-Celtic links the Goidelic insular languages (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx) with continental Hispano-Celtic. In P-languages the Proto-Celtic labiovelar *kʷ became p; in Q-languages it became k.

Overview. Like Scottish Gaelic, Manx was an offshoot of Irish which arrived into the island of Man around 500 CE, as part of the Irish expansion into Britain. Manx diverged from Scottish Gaelic in the 15th century to constitute a separate language, after the incorporation of Man into the English orbit and the severance of its ties with other Gaelic speaking communities.

Due to its isolation, Manx preserved archaisms from Old and Middle Irish lost in other branches of Gaelic but, at the same time, introduced innovations, particularly in the verbal system.

Distribution: Manx was spoken by the majority of inhabitants of the Isle of Man until the 19th century, when it was displaced by English.

Status. Extinct. The lifespan of the language was from the 15th to the 19th centuries.

Oldest Documents

c. 1500. A history of Manx, starting with the introduction of Christianity, called Manannan Ballad or “Traditionary Ballad”.

1610. A version of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, translated into Manx by a Welsh bishop who used an orthography based on that of English.

1707. The Principles and Duties of Christianity, a bilingual text, by Thomas Wilson.

1728-75. A complete translation of the Bible (Old and New Testaments), done by various authors. A major source for our knowledge of the language.

Periods

16th-17th c. Early Manx, as exemplified in the translation of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer

18th c. Classical Manx, represented by the Bible translation.

19th-20th c. Late Manx, represented by the folk stories written by Ned Beg Hom Ruy.

Phonology

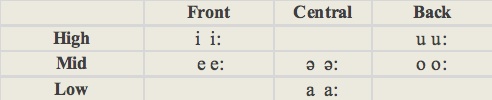

Vowels: Manx has 12 simple vowels and 10 diphthongs.

a) Monophthongs (12): include six short vowels, each having a contrasting long variety.

b) Diphthongs (10): iə, ei, eu, əi, əu, ai, au, ui, uə, oi

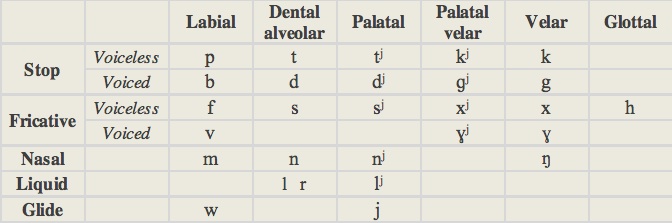

Consonants (28). A number of Manx consonants (dental-alveolar and velar) can be articulated in neutral or palatalized form (indicated by j)

Stress: it generally falls on the first syllable of a word, but in many cases, stress is attracted to a long vowel in the second syllable.

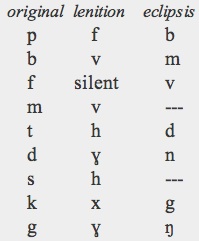

Initial consonant mutation. Manx shows, like all Celtic languages, initial consonant mutation by which the initial consonant of a word is altered according to its morphological and/or syntactic environment. The most frequent type is lenition in which some initial consonants of a word change into a fricative. Only nine consonants can be lenited: p, b, f, m, t, d, s, k, g. Another type of initial mutation is eclipsis which affects seven of the above consonants.

Script. Manx used the Latin script, based on English orthography. The Manx alphabet didn’t distinguish adequately palatalized consonants.

Morphology

-

Nominal. Adjectives usually follow the noun they qualify and are usually not inflected for gender and case.

-

•gender: masculine (unmarked), feminine.

-

•number: singular, plural.

-

•case: Manx lost all case inflections, except a genitive singular applied to a minority of nouns, and the occasional vocative.

-

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, possessive, reflexive, relative, interrogative, indefinite.

-

Personal pronouns exist in simple and emphatic forms. They may function both as subject and direct object, and combine, as suffixes, with prepositions. The simple forms are: mee (‘I’), oo (‘you’), eh (‘he’), ee (‘she’), shin (‘we’), shiu (‘you’), ad (‘they’).

-

Demonstrative pronouns recognize three deictic degrees: proximal (‘this’), intermediate (‘that?), and distal (‘that yonder’). The three demonstratives, shoh, shen, shid, don’t have plural forms and require the article before the noun.

-

The reflexive pronoun hene (‘self’) can be attached to all pronominal forms.

-

The interrogative pronouns are quoi (‘who?, whom?’) and cre/c'red (‘what?’).

-

Indefinite pronouns are made by adding erbee (‘any’) or ennagh (‘some’) to a noun or interrogative pronoun. For example: quoi erbee (‘whoever’), cre erbee (‘whatever’), peiagh ennagh (‘someone, somebody’), red ennagh (‘something’).

-

•article: Manx has a definite article but not an indefinite one. It has singular (y or yn) and plural forms (ny), but it doesn't distinguish gender. It may be used with numerals and demonstrative pronouns, and can take the role of a possessive adjective.

-

Verbal. The verbal stem is identical to the imperative singular.

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s (masc, fem); 1p, 2p, 3p.

-

•tense: present, preterite (simple past), imperfect, perfect, pluperfect, future, future perfect (rare), conditional, past conditional.

-

Verbs generally form their finite forms by means of periphrasis: inflected forms of the auxiliary verb ve (‘to be’) or jannoo (‘to do’) are combined with the verbal noun of the main verb. Only the future, preterite, conditional, and imperative can be formed directly by inflecting the main verb, though periphrastic forms are preferred.

-

The auxiliaries and irregular verbs make a distinction between independent and dependent forms. Independent forms are used when the verb is not preceded by any particle; dependent forms are used when a particle does precede the verb.

-

•mood: indicative, imperative, subjunctive.

-

•voice: active, passive.

-

•non-finite forms: verbal noun, past participle.

-

Manx doesn't have an infinitive. Its role is supplied by the verbal noun which is formed by adding a suffix to the verb stem, like -ey, -aghey and others. The verbal noun plays an essential role in conjugation and, can also express purpose and be part of impersonal or passive constructions. The past participle is made by suffixing -t or -it to the stem. It can be used attributively (as an adjective), predicatively (to indicate a state) or with -geddyn (‘to get’) to express an imminent or progressive action.

Syntax

Manx word order is Verb-Subject-Object. Verbal conjugation is mainly periphrastic with an auxiliary verb marking the tense and a separate pronoun person and number. When an auxiliary verb is used, it precedes the subject, while the verbal noun comes after the subject. The direct object precedes the indirect one. Manx uses prepositions to indicate syntactical relations which are suffixed with personal pronouns to indicate their object.

Within the noun phrase, the order of its components is quite strict: preposition, article or possessive pronoun, numeral, adjectival prefix, noun, adjective, demonstrative.

Lexicon

The main corpus of Manx is Celtic but there also loans from Latin (ecclesiastical terms), Old Norse (a few words related to fishing and seamanship), French (many words including terms for government and administration), and English.

Basic Vocabulary

one: nane

two: jees

three: tree

four: kiare

five: queig

six: shey

seven: shiaght

eight: hoght

nine: nuy

ten: jeih

hundred: keead

father: ayr

mother: moir

brother: braar

sister: shuyr

son: mac

daughter: 'neen

head: kione

eye: sooill

foot: cass

heart: cree

tongue: çhengey

Literature

Manx literature consists mainly of religious works and translations. Among the former, it is noteworthy a body of about 150 religious folksongs called carvals. Secular folklore stories were authored by Ned Beg Hom Ruy in the 19th. century (Edward Faragher, 1831-1908), but published only in 1982.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Manx'. G. Broderick. In The Celtic Languages, 305–356. M. J. Ball & N. Müller (eds). Routledge (2009).

-

-Practical Manx. J. K. Draskau. Liverpool University Press (2008).

-

-Celtic Culture. A Historical Encyclopedia (5 vols). J. T. Koch (ed). ABC-CLIO (2006).

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania