An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Alternative Names: Mapudungu, Mapuche, Araucanian.

Name Origin: Mapudungun means in this tongue ‘language of the land’, from mapu ('land') and dungun ('language'). Mapu-che, 'people of the land' is the self-designation of the indigenous community which is also used (less correctly) as the name of their language. Araucanian derives from Arauco, the name of a region whose etymology is uncertain.

Classification. Mapuche is a language isolate. Its relationship to a number of South American and Meso-American families has been proposed but rejected by the majority of scholars.

Overview. Mapudungun was virtually the only language in central and southern Chile at the arrival of the Spanish conquerors in contrast to the linguistic diversity prevailing across all of the Americas. From Chile, the Mapuche entered Patagonia and the pampas of Argentina for raiding expeditions and to establish colonies. The Mapuche resisted fiercely the intrusion on their land and as a result Mapudungun is, with at least a quarter-million speakers, one of the largest South American indigenous tongues (though far behind Quechua, Aymara and Guarani). It shares some features with Andean languages but others, like interdental consonants, lack of case, and noun incorporation, are not found in them.

Distribution. It is spoken in southern Chile, namely in the provinces of Biobío, Malleco, Cautín, Arauco and Valdivia (region of Los Lagos) and in several locations in the Argentinian pampas and Patagonia (particularly in Neuquén). The geographical, social and economic centre of the Mapuche territory is the city of Temuco. Many Mapuche have migrated to central Chile, including to the capital Santiago.

Speakers. A conservative estimate is 200,000 in Chile and around 50,000 in Argentina.

Status. The Mapuches have lost control of their own territory and had become a discriminated minority in the Chilean and Argentinian societies. Most of them are small-scale farmers but many have had to migrate to the big cities, Santiago in particular, with the consequent loss of their language and culture. Successive Chilean governments persist in their oppressive policies, and to resist their loss of autonomy the Mapuche have grouped themselves into many small political organizations.

Varieties. The main variety is Central Mapudungun in south-central Chile. An important dialect is Pehuenche located to the east of the above. Other dialects in Chile are Picunche and the divergent Huilliche. The Argentinian dialects show some influence from Tehuelche or other local languages but they are, otherwise, close to their Chilean relatives.

Oldest Documents

-

1606.Arte y Gramatica General de la Lengua que Corre en Todo el Reyno de Chile, by the Jesuit priest Luis de Valdivia, is the first Mapuche grammar.

-

1764.A grammar by Febré.

-

1777.Another grammar, composed in Latin, by Havestadt.

-

1903.An outstanding grammar by the Bavarian missionary Félix José de Augusta.

-

1916.A remarkable dictionary by Augusta.

Phonology

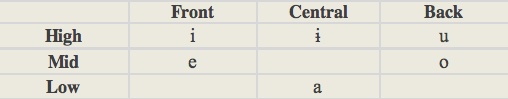

Vowels (6). Mapudungun has six vowels; there are no length distinctions. Vowel sequences are common. [ɨ] when unstressed is realized as a schwa [ə].

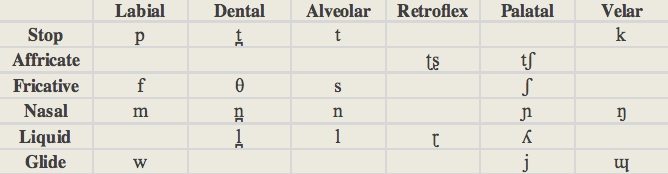

Consonants (22): All stops, affricates and fricatives are voiceless. The dental and alveolar series contrast only in conservative speech; most speakers have only an alveolar series. Consonant sequences occur only in intervocalic position and have no more than two consonants.

Stress. Tends to fall on the penultimate mora.

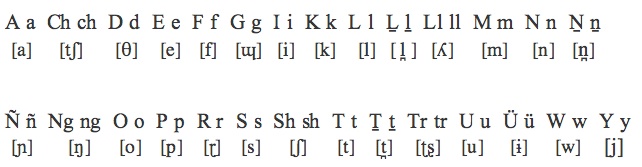

Script and Orthography. There is no standard orthography. Three alphabets are currently in use (Unificado, Raguileo, Azümchefe). We display hear the Unificado alphabet that has a one-to-one correspondence between letters and phonemes. It consists of 28 symbols (their equivalent in the International Phonetic Alphabet is shown between brackets):

Morphology

Mapuche's nominal morphology is simple but its verbal morphology is rich and has a productive system of noun incorporation.

-

Nominal. Nouns are not marked for case or gender, and number marking is restricted to some nouns.

-

•gender: there is no grammatical gender. Natural gender is indicated by lexical means.

-

•number: animate nouns are pluralized with the preposed element pu:

-

wentru (man) → pu wentru (men)

-

Inanimate nouns are not usually marked for plural. Modifiers, and in particular adjectives, take the plural suffix -ke:

-

füchake che (old people)

-

old-PL people

-

The suffix -wen is used to refer to a generic pair; it is applied to one member of the pair while the other is understood:

-

püñeñwen (mother and child)

-

child-PL

-

•pronouns: personal, possessive, demonstrative, interrogative.

-

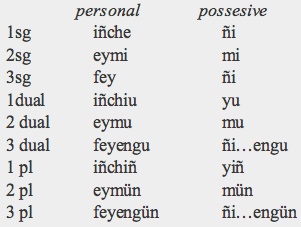

Personal and possessive pronouns distinguish three persons (first, second, and third) and three numbers (singular, dual, and plural).

-

Possessive pronouns occur before nouns and nominalized verbs and are formally related to personal pronouns.

-

They are independent words and can be separated from the noun by another modifier, such as an adjective. They can be preceded by a personal pronoun for emphasis or disambiguation (e.g. in the case of ñi, which is used both for first person singular and for third person).

-

In the following examples, the noun ruka (‘house’) is preceded by just a possessive in the first case, and by a personal pronoun + possessive in the second case (emphatic).

-

mi ruka or eymi mi ruka (your house)

-

When the possessive is accompanied by a personal pronoun, the 3rd person dual and plural markers (engu and engün, respectively) are not used:

-

ñi ruka engu or feyengu ñi ruka (the house of the two of them)

-

Genitive constructions are like this:

-

tüfachi wentru ñi ruka (this man's house)

-

this man his house

-

Demonstrative pronouns recognize three deictic degrees: tüfa (‘this’), tüfey (‘that’), tüye (‘that’ [distant]). When used as modifiers, the demonstratives must be followed by the adjectivising suffix chi.

-

Some interrogative pronouns derive from the verb root chum: chumül (‘when?’), chumngechi (‘how?’), chumngelu (‘why?’). Others derive from related roots: chem (‘what?/which?’), chew (‘where?’). ‘Who?’ is said iney or iniy.

-

Verbal. Mapuche's verbal morphology is exceptionally rich, agglutinative and predominantly suffixing. The conjugated verb includes the root followed by optional derivational suffixes and an inflectional block expressing person and number of the subject, object, mood, tense, aspect, negation and nominalization.

-

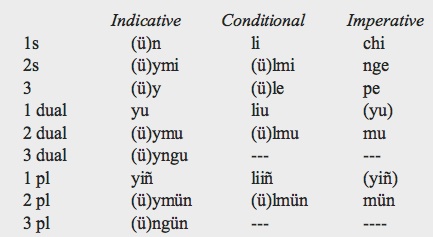

•subject marking: three persons (first, second, and third) and three numbers (singular, dual, and plural) are distinguished. In the 1st and 2nd persons, number marking is obligatory but in the 3rd person is optional. The subject markers in the three moods of Mapuche are:

-

There is no imperative form for the first person non-singular. The indicative 1st dual and 1st plural may be used adhortatively.

-

•object marking: in transitive verbs if the object is a 3rd person it is marked by either of two object markers, -fi- or -e-, which are mutually exclusive. The referent of -fi- is a third person, animate or inanimate, which plays a less dominant role in the discourse than the referent of the subject. The latter is in focus at the moment of speaking. The suffix -fi- does not differentiate number, its referent may be singular, dual or plural. Personal pronouns can be used to specify the number of the direct object.

-

The infix -e- indicates that the referent of the subject is the patient and not the agent of the event. It is a kind of passive voice in which the agent is known. In this construction the agent is marked by the suffix -(m)ew which refers to a third person unmarked for number, animate or inanimate. When the agent is not expressed a different kind of construction is required (employing the passive suffix -nge).

-

ḻangüm-fi-n (I killed him)

-

kill-OP-SUBJ1s

-

ḻangüm-e-n-ew (He killed me/I was killed by him)

-

kill-OA-SUBJ1s-AG3rd

-

OP: object patient, OA: object agent (-ew co-occurs with, and modifies, -e), SUBJ: subject, AG: agent

-

•mood: indicative, conditional, imperative.

-

The indicative marker is -y-, and the conditional marker is -l-; the imperative has no specific marker. Mood markers precede the person and number markers of the subject and are not separable from them (see above subject markers).

-

•tense: unmarked tense, past, future.

-

There is no real present tense. If the verb expresses an action, the unmarked tense is usually translated as a preterite. If, on the other hand, it expresses a state or quality, it is generally translated as present. The future is marked with the infix -a-. The past tense, marked with the -fu-, implies that an event is completed and that its results are no longer valid, nor relevant. The markers -a- and -fu- can be used together (-a-fu-) in order to indicate a future of the past.

-

•aspect: perfective, habitual, progressive, continuative, discontinuative, etc.

-

Most verbs have a perfective sense if they are not marked for aspect. An habitual action may be marked by -ke-. The continuative infix -ka- indicates that a situation is continued beyond a certain moment. An action that is no longer done is expressed by the discontinuative -fu-. A progressive action by -meke- or -petu- or -nie-.

-

•derivational extensions: the Mapuche verb can contain a large variety of derivational extensions including evidential, modal, aspectual and spatial affixes. Some of them tell us that the subject witnessed an action or that an action was sudden or repetitive. Others, that an action was causative or reflexive or that the action was passive and the agent unknown.

-

The main spatial markers of Mapuche are -me-, -pa- and -pu-. Me indicates motion away from the speaker, pa indicates motion towards the speaker and pu a location remote from the speaker without a previous motion. Circular motion can be indicated by employing the infixes -yaw-/-kiaw-.

-

•negation: is indicated by three different markers used in the indicative (la), imperative (ki) and conditional (nu) moods. The latter is used also in nominalizations, nominal expressions and negative predicates.

-

•nominalization: nominalizing suffixes are used mainly in non-finite verb forms but sometimes also in conjugated verbs. -el is primarily used as a passive participle, indicating the patient of the event, -lu denotes the subject of an event. The suffix -m refers to a place or an instrument.

-

•compounding: verbal roots may be compounded with other verbal roots, with nouns, and also objects may be incorporated (noun incorporation).

Syntax

Almost all word-order patterns in the sentence are attested. Mapudungun is head-final at both the nominal phrase and clause levels. In the nominal phrase this fixed order is followed: pronominal modifier-numeral-adverb-adjective-noun.

-

tüfachi küla lüq ruka (These three white houses)

-

this three white house

Many verbs carry spatial information, rendering adpositions superfluous. A number of particles express the attitude of the speaker towards what has been said. They are used in questions or affirmative sentences. They follow the noun or verb phrase and they can take sentence final position.

Lexicon

Mapudungun has borrowed from Aymara, Quechua and Spanish. The numeral system shows the influence of Quechua/Aymara but not in the first ten numbers.

Basic Vocabulary

one: kiñe

two: epu

three:küla

four: meli

five: kechu

six: kayu

seven: regle

eight: pura

nine: aylla

ten: mari

hundred: pataka (from Quechua/Aymara)

thousand: warangka (from Quechua/Aymara)

father: chaw

mother: ñuke

brother (of a woman): lamngen

brother (of a man): peñi

sister (of a woman or man): lamngen

son (of a man): fotüm

son (of a woman): püñeñ

daughter (of a man): ñawe

daughter (of a woman): püñeñ

head: longko

face: ange

eye: nge

hand: kuwü

foot: namun

heart: piuke

tongue: kewün

Key Literary Work

One unique document to understand Mapuche culture in the turbulent times of the second half of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th, is the autobiography of Pascual Coña (1840-1927), a Mapuche who told his life in Mapudungun to the missionary Ernesto Wilhelm de Moesbach. He published it in a bilingual edition (Mapudungun-Spanish).

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-A Mapuche Grammar. I. Smeets. Mouton de Gruyter (2008).

-

-'Araucanian or Mapuche'. W. F. H. Adelaar & P. C. Muysken. In The Languages of the Andes, 515-544. Cambridge University Press (2004).

-

-El Mapuche o Araucano. Fonología, gramática y antología de cuentos. A. Salas. MAPFRE (1992).

-

-Mapudungun (Mapuche or Araucanian). F. Zuñiga. Lincom Europa (2000).

-

-Vida y costumbres de los indígenas Araucanos an la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. P. E. W. de Moesbach. Santiago de Chile: Imprenta Universitaria (1936).

Mapudungun

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania