An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Overview. Mayan is the largest family of Meso-American indigenous languages. There are about thirty of them spoken by 5.5 million people in southern Mexico and Central America. They are the descendants of the ancient Maya who developed, long before the arrival of the Europeans, a great civilization based on corn cultivation and expressed in monumental architecture, sculpted stelae and mural and vase paintings. They had a full writing system and a highly sophisticated calendar.

Distribution. Mayan languages are spoken in Guatemala, Belize and Southern Mexico (Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatán, Quintana Roo). Huastec is a language island in central Mexico (San Luis Potosí and Veracruz) separated by more than 1,500 kilometers from its Mayan relatives. There are also some speakers in northern El Salvador and northern Honduras. Many Mayan speakers have migrated to California, Florida, Texas, and Arizona.

Speakers. Approximately 5.5 million in total. Two million Maya speakers live now in Mexico, about 3.4 million in Guatemala, 20,000 in Belize and a handful in El Salvador and Honduras.

Classification. Mayan languages are divided into six branches: Huastecan, Yucatecan, Cholan-Tzeltalan, Kanjobalan-Chujean, Mamean and Quichean. The last two are closely related. Huastecan branched off first followed by Yucatecan and, later, by the other branches. Number of speakers is shown between brackets; a cross indicates an extinct language.

-

1)Huastecan (165,000)

-

• Huastec (165,000) in San Luis Potosí and Veracruz.

-

• Chicomuceltec♰, formerly in Chiapas and Guatemala.

-

2)Yucatecan (815,000)

-

a) Yucatec-Lacandon

-

• Yucatec (800,000) in Yucatán Peninsula and Belize.

-

• Lacandon (560) in Chiapas.

-

b) Mopán-Itza

-

• Itza (nearly extinct) in Guatemala (Petén).

-

• Mopán (14,200) in eastern Guatemala (Petén) and Belize.

-

3)Cholan-Tzeltalan (1,140,000)

-

a) Cholan

-

• Chorti (30,000) in Guatemala (eastern border with Honduras).

-

• Chontal (38,000) in Tabasco.

-

• Ch'ol (215,000) in Chiapas and Tabasco.

-

b) Tzeltalan

-

• Tzotzil (405,000) in Chiapas.

-

• Tzeltal (450,000) in Chiapas.

-

4)Kanjobalan-Chujean (300,000)

-

a) Chujean

-

• Tojolab'al (50,000) in Chiapas.

-

• Chuj (50,000) in Guatemala (Huehuetenango).

-

b) Kanjobalan

-

• Jakaltek (100,000) in Guatemala (Huehuetenango) and Chiapas.

-

• Kanjobal or Q'anjob'al (100,000) in western Guatemala.

-

• Mocho or Motozintlek (140) in Chiapas (Mexico-Guatemala border).

-

5)Greater Mamean (633,000)

-

a) Ixilan

-

• Ixil (70,000) in Guatemala (Quiché).

-

• Awakatek (18,000) in Guatemala (Huehuetenango).

-

b) Mamean

-

• Mam (540,000) in western Guatemala (Huehuetenango, San Marcos,

-

Quezaltenango).

-

• Tektiteko or Teko (5,000) in Guatemala (Tectitán municipality in Huehuetenango)

-

and Chiapas.

-

4)Greater Quichean (2,500,000)

-

a) Kekchian

-

• Kekchi or Q'eqchi' (825,000) in Guatemala (Northern Alta Verapaz, southern Petén).

-

Some speakers in Belize and El Salvador.

-

b) Uspantecan

-

• Uspantec (3,000) in Guatemala (Quiché, San Miguel Uspantán).

-

c) Pocomam

-

• Pocomam or Poqomam (50,000) in Guatemala (Jalapa and close to Guatemala City).

-

• Pocomchi or Poqomchi' (90,000) in Guatemala (Alta Verapaz).

-

d) Quichean

-

• Sipacapa (8,000) in Guatemala (San Marcos).

-

• Sacapultec (15,000) in Guatemala (Quiché).

-

• Tzutujil (85,000) in Guatemala (south of Lake Atitlán).

-

• Cakchiquel or Kaqchikel (450,000) in south Guatemala.

-

• Achi (85,000) in Guatemala (Baja Verapaz).

-

• Quiche or K'iche' (900,000) in central and south Guatemala.

In summary, the largest Mayan languages are: Yucatec in the Yucatan peninsula, Tzeltal and Tzotzil in Chiapas, Ch'ol in Tabasco and Chiapas, Mam and Q'anjob'al in west Guatemala, K'iche' and Kaqchikel in central and south Guatemala, Q'eqchi' in north Guatemala. Another important language is Huastec spoken in central Mexico.

Oldest Documents

-

•Most Maya inscriptions date from the "Classical Period" that starts in the first centuries CE. In the Preclassic period inscriptions are rare and short. Very recently, a sample of Maya hieroglyphic writing was discovered in the ruins of San Bartolo, Guatemala, dating back to 300-200 BCE, being the earliest known so far.

-

•Another early inscription is on a stela found in El Baúl, in the Pacific Coast of Guatemala, dating from 36 CE.

-

•The earliest known lowland hieroglyphic text is on Stela 29 from Tikal in northern Guatemala, which bears a date of 6 July 292 CE.

SHARED FEATURES

-

✦ Phonology

-

-Syllable structure. Mayan morphemes can have the following syllabic shapes: CVC (the most common type), CV, VC, and V. Sequences of vowels or consonants within words are not permitted. There are, however, some initial consonant clusters, most of them originated from prefixes which have lost their vowel.

-

-Vowels: Mayan languages have five vowel qualities, namely i (high-front), u (high-back), e (mid-front), o (mid-back), a (low-central). Some languages have also long vowels.

-

-Consonants: All Mayan languages have labial, alveolar and velar series of simple and glottalized stops. Uvular and glottal stops, and a labial implosive are also widespread. They also have alveolar and palatal affricates, simple and glottalized. Thus, consonant systems usually have:

-

• Voiceless Stops: p (bilabial), t (alveolar), k (velar), q (uvular), ' (glottal).

-

• Glottalized stops: p' (bilabial), t' (alveolar), k' (velar), q' (uvular).

-

• Voiced stops: b' (labial) implosive.

-

• Voiceless Affricates: ts (alveolar), tʃ (palatal).

-

• Glottalized affricates: ts' (palato-alveolar), tʃ ' (palatal).

-

• Voiceless fricatives: s (alveolar), ʃ (palatal), x velar or uvular, h (glottal) in some languages.

-

• Nasals: m (bilabial), n (alveolar).

-

• Liquids: l (alveolar), r (alveolar).

-

• Glides: w (bilabial), j (palatal).

-

-Tones: Yucatec, Tzotzil and Uspantec have two tones (high and low) without combinations.

-

✦ Morphology

-

-These languages belong to the agglutinating type and morphemes have clear boundaries. Stems are usually monosyllabic.

-

-Inflection and derivation add prefixes or suffixes to the stem. Derivational elements are many and very productive. Noun compounding is extensive. Reduplication is commonplace; it is used to express plurality, intensity of action or repeated action.

-

Nominal

-

-Like in other Meso-American languages, gender is not marked in Mayan. Number is not marked on nouns either except in those referring to people in some languages e.g. in K'iche': ixoq (‘woman’), ixoqiib (‘women’). There are very few definite markers or none.

-

-Nominal possession is expressed in almost all languages by a possessive prefix joined to a noun. Most possessives distinguish 1st, 2nd and 3rd persons, singular and plural. Some have different forms for 1st person plural inclusive and exclusive.

-

-Maya languages have noun classifiers based on semantic aspects, referring to persons, animals, trees, plants, long slender objects, flat objects, round objects, metal and stone objects, water and related things, etc. There are also numeral classifiers that co-occur with numerals and distinguish between persons, animals and inanimate objects; in some languages classifiers are affixed to numerals while in others they are independent.stela

-

Verbal

-

-Plurality, aspect, tense and mood may be marked on the verb. Besides, by means of affixes, verb stems can adopt the following forms: transitive, intransitive, causative, passive.

-

-Tense is less important than aspect. Tense systems are simple. In Jakaltek, for instance, there are just two tenses: past and non-past. Non-past is used for present, habitual or repetitive events, and with a special suffix to future events. Mam has also two tenses, future and non-future, the latter referring to events happening at any time (even in the future).

-

-Aspect refers to the manner the action is performed. The aspects most frequently found in Mayan are: progressive (ongoing action), continuative (a situation is continued beyond a certain moment), habitual, completive (completed action), incompletive (the action has not been completed), perfective (an action completed in reference to a particular moment), potential (a possible action).

-

-Moods include, besides the indicative, simple imperative, polite imperative, exhortative and subjunctive. In some Mayan languages aspect and mood are mutually exclusive.

-

-Direction, motion and location can be indicated by the use of affixes, clitics and auxiliary verbs. Otherwise, by directional particles.

-

-Positional verbs are special verbs that are formally and semantically different from others. They refer to positions (sitting, standing, lying, kneeling, bowing, etc) or physical states (clean, dry, long, etc.) of human beings, animals, and inanimate objects.

-

-Most Mayan languages have ergative systems in which subjects of intransitive verbs are marked by the same forms that mark the object of a transitive verb, while the subject of transitive verbs is marked differently.

-

✦ Syntax

-

-In most Mayan languages the verb comes first in the sentence followed by the object or the subject. Thus, word order is:

-

•Verb-Object-Subject (VOS) in Yucatecan, Tzotzil, and Tojolabal.

-

•Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) in Mamean, Q'anjob'al, Jakaltek and one Chuj dialect.

-

-In some languages, like Huastec, Tzeltal, Chuj, Akatek and most Quichean, word order oscillates between VOS and VSO. In Ch'orti' the order is SVO, perhaps due to Spanish influence.

-

-VSO order is correlated with the presence of prepositions. Nouns precede the possessor and the adjective, and are preceded by numerals.

Writing System

The Maya created a hieroglyphic script that was in continuous use from the last centuries BCE until the second half of the sixteenth century, when it was replaced by the Latin-based alphabet introduced by the Spaniards. It was a mixed writing system, consisting of both logographic and syllabic signs. The total number of different signs that have been identified ranges between 650 and 700. The reading order of an ancient Maya text is from top to bottom and from left to right in paired columns.

Lexicon

Mayan languages have loanwords from Nahuatl, Spanish and English.

Basic Vocabulary

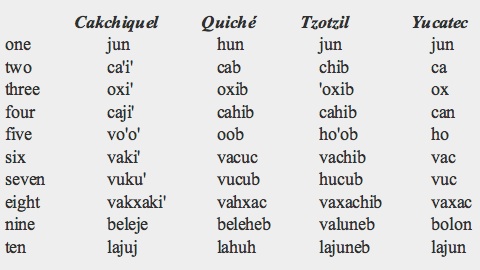

Due to derivational processes Mayan languages' vocabularies are organized into extensive word families. The numerals in some of the main languages are:

Literature

In Quiché

-

✴Popol Vuh (The Book of Counsel) was written originally in Mayan hieroglyphs before the arrival of the Spanish and transcribed into the Roman alphabet in the 16th century. It narrates the myths and history of the Quiché people, starting with the creation of the world, following with the successive creations of different kinds of men, a war of gods, and the origin, migrations and wars of the Quiché. It is the most significant text of ancient Meso-American literature that has been preserved.

-

✴Rabinal Achí, though recorded in the 19th century, is a Pre-Hispanic drama. It is a sample of ancient theatrical representations in Yucatec societies including music, dancing and acting.

In Yucatec

-

✴Books of Chilam Balam are a series of nine books composed in towns of the Yucatán Peninsula. Their subject is heterogeneous and includes matter from native and Spanish origin. From the former: historical accounts, religious texts, explanations of the calendar, astrology and medicine treatises, prophecies and rituals. From the latter, literary and religious texts translated into Yucatec.

-

✴The Book of Songs of Dzitbalché is a collection of fifteen ancient poems that were accompanied by music and dance; some of them are religious or ritual in nature, others are love songs.

In Cakchiquel

-

✴The Annals of the Cakchiquels, written at the end of the 16th century, collect the oral traditions of this people, including mythology and history with a section devoted to the Spanish conquest.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-The Mesoamerican Indian Languages. Jorge A. Suárez. Cambridge University Press (1983).

-

-'Mayan Languages'. J. M. Maxwell Tulane. In Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, 705-709. K. Brown & S. Ogilvie (eds). Elsevier (2009).

-

-Introducción a la Gramática de los Idiomas Mayas. N. C. England. Cholsamaj (2001).

-

-Maya Glyphs (Reading the Past). S. D. Houston. British Museum Publications (1989).

Mayan Languages

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania