An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Alternative Name: Afaan Oromo, Galla (pejorative).

Classification: Afro-Asiatic, Cushitic, East Cushitic, Southern Lowland East Cushitic, Oromoid.

Cushitic is a highly diverse group of languages spoken in the Horn of Africa and one of the six branches (or families) of the Afroasiatic phylum; it is divided into North, Central and East Cushitic which is further subdivided into Highland and Lowland languages. Other important Lowland East Cushitic members, besides Oromo, are Somali and Afar.

Overview. Oromo is the fourth major language of Africa (after Arabic, Hausa and Yoruba) and the major regional one of Ethiopia (Amharic is the national language). It is spoken by the Oromo, one of the two largest ethnolinguistic groups of Ethiopia whose homeland was in the southeast of the country. From there, they migrated in successive waves, during the 16th century CE, occupying aggressively most of the south and parts of the center and west. Those Oromo that still live in the south are pastoralists and pagan but others had intermarried with various ethnic groups and become farmers and either Muslims or Christians. Until recently, Oromo was a vernacular language rarely written and lacking its own script. It has tones and glottalized consonants, a well-developed case-system, subject-object-verb order and a focus marking system.

Distribution. It is spoken for the most part in Ethiopia, particularly in the Oromia region, the largest of the nine ethnically-based administrative divisions of the country which extends over most of the south and center. Also, in north and eastern Kenya, and by only a small number of speakers in southern Somalia.

Speakers. Close to 27,5 million people speak Oromo as a mother tongue in the following countries: Ethiopia (27,000,000), Kenya (300,000), Somalia (45,000).

Varieties. There are five main dialect groups: Central-Western (Macha, Tuulamaa, Wallo, Raya) which is the most numerous, Eastern (Harar or Qottu Oromo), Southern (Booranaa, Guji, Arsi, Gabra) spoken in southern Ethiopia and adjacent areas of Kenya, Orma spoken in Kenya along the Tana river and in southern Somalia, and Waata spoken along the Kenyan coast south of Orma. There is no standard though the Central-Western variety tends to become the basis for one.

Status. Until 1974, when the Ethiopian monarchy fell, Oromo was only a spoken language, ostracized in education and in the media. Since, it is written and printed, being designated in 1992 as an official language in the Oromo region of Ethiopia.

Phonology

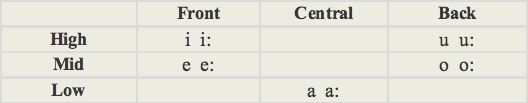

Vowels (1o). Oromo has the typical Eastern Cushitic set of five short and five long vowels. Vowel length is phonemic.

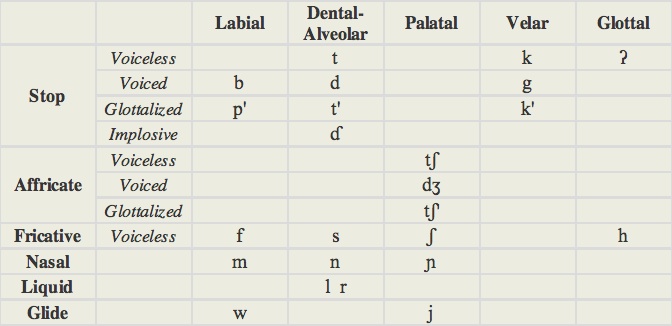

Consonants (24). Consonants can be short or long (except for ʔ and h), and consonant length is phonemic. Consonant clusters of up to two consonants are possible but longer ones are always broken by the introduction of an epenthetic vowel (usually i). Like many Afroasiatic languages, Oromo has 'emphatic' consonants pronounced glottalized (ejectives) or even as an implosive.

Tones: Oromo has two tones, high and non-high, which don't serve to make lexical distinctions but morphological or syntactical ones. Tones are not marked in the script. As Proto-Afroasiatic was probably non-tonal, Oromo must have acquired them through contact with Nilo-Sharan or Niger-Congo languages.

Script and Orthography.

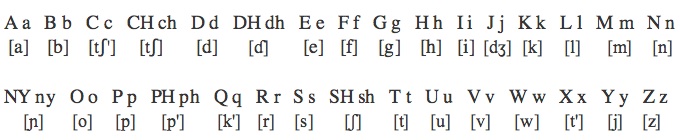

Oromo was written first in the Ethiopian syllabary used for Classical Ethiopian, Amharic and Tigrinya. In 1974 it was replaced by a Roman-based script, called Qubee. It contains 31 symbols of which 5 are digraphs (their equivalent in the International Phonetic Alphabet is given between square brackets):

-

•Long vowels are indicated by doubling. A long consonant is also indicated by doubling except when it is represented as a digraph.

-

•p, v, z occur in loanwords and in some dialects.

-

•the glottalized and implosive stops are represented: [p'] as ph, [t'] as x, [ɗ] as dh, [k'] as q.

-

•the glottal stop [ʔ] is represented by an apostrophe.

-

•the affricates are represented: [tʃ] as ch, [dʒ] as j, [tʃ '] as c.

-

•the fricative [ʃ] is represented with the digraph sh.

-

•the nasal [ɲ] is represented with the digraph ny.

-

•the glide [j] is represented as y.

Morphology

-

Nominal. Nouns are marked for case, number and, sometimes, gender.

-

•case: absolutive, nominative, genitive, dative, instrumental, locative, ablative.

-

Nominative and absolutive are the fundamental cases which elicit agreement between the constituents of the noun phrase. The unmarked absolutive is the citation form, functioning as predicative or direct object. The nominative marks the subject with suffixes or tones. Other case functions are only marked at the end of the phrase and do not require agreement. The genitive case (expressing possession) is indicated by lengthening a final vowel usually with high tone. Optionally, a possessive particle (kan with masculine nouns, tan with feminine) may also be used before the possessive noun or phrase.

-

•gender: masculine, feminine. Except in some dialects or when referring to people, nouns are not marked for gender.

-

•number: singular, plural. Plurals are formed through the addition of suffixes. The most common is -oota, others are -wan, -een and -(a)an. Besides, there are some particulative forms (when the noun is specially marked to single out a particular item from a group).

-

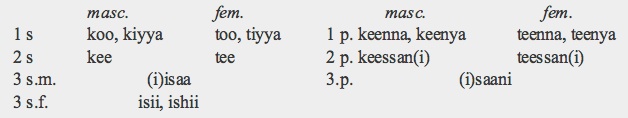

•pronouns: personal, reflexive, possessive, demonstrative, interrogative.

-

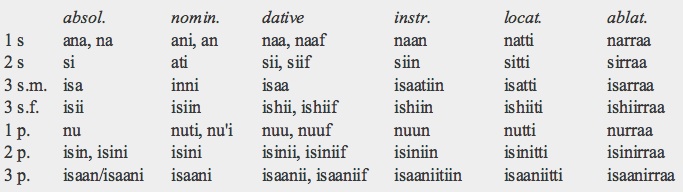

Personal pronouns have seven forms for each case distinguishing three persons, two numbers (singular and plural), and gender only in the third person singular. Besides the absolutive, they are declined in the nominative, dative, instrumental, locative and ablative cases:

-

-

-

The reflexive pronoun of(i) or if(i), meaning 'self', is inflected for case but not for person, number or gender. It can be replaced by the noun mataa ('head') suffixed with possessive adjectives.

-

Possessive pronouns distinguish gender of the possessed noun in the 1st and 2nd persons (except in western dialects):

-

Demonstratives make a two-way distinction between proximal and distal and are inflected in several cases; they distinguish gender in the proximal pronoun, in some dialects, but not number. The absolutive of 'this/these' is kana (m), tana (f) and of 'that/those' is san; their nominative is, respectively, kuni (m), tuni (f) and suni.

-

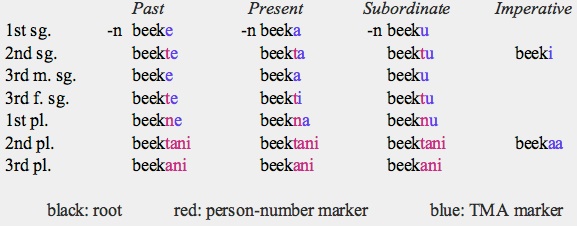

Verbal. Verbs are inflected for tense-mood-aspect (TMA), person-number and voice by adding suffixes to the root. After the root, up to two optional suffixes may be added to mark voice, followed by a person-number marker and a TMA suffix.

-

•person and number: 1st and 3rd singular masculine are identical; the 2nd singular and 3rd singular feminine are identical too.

-

•tense-mood-aspect (TMA): present, past, subordinate (or subjunctive), imperative-jussive.

-

TMA is marked by vowels placed after the person marker:

-

•the past by e

-

•the present by a (except in the 3rd fem. sing. where it is i)

-

•the subordinate by u.

-

-

The present can only be used in main clauses, so in dependent clauses it is replaced by the subordinate, The subordinate form is also used as a negative present with the particle hin, and as a jussive with the particle haa. The negative past and the negative jussive are both invariable with respect to person. As an example, we show above the conjugation of the verb beek ('to know').

-

The first singular requires an -n suffix in the preceding word (a reduced form of the pronoun ani). The 2nd and 3rd plural forms are identical in the past, present and subordinate. In the same persons, the present has the alternative forms beektu and beeku.

-

-

•voice/derived stems: middle (or autobenefactive), passive, causative, intensive.

-

The autobenefactive, passive and causative are indicated by suffixes added to the basic stem. The intensive (or frequentative) is formed by partial reduplication of the stem.

Syntax

Cushitic languages have Subject-Object-Verb word order. Dependent clauses generally precede the main one except for relative clauses that follow their head noun. Oromo marks the focus of a phrase by means of clitic particles distinguishing predicate and non-predicate focus.

Basic Vocabulary

one: tokko

two: lama

three: sadi

four: afur

five: shan

six: jaha

seven: torba

eight: saddeet

nine: sagal

ten: kudhan

hundred: dhibba

father: abbaa

mother: haadha

brother: obboleessa

sister: obboleettii

son: ilma, ilmo

daughter: intala

head: mataa

eye: ija

foot: miillaa

heart: onnee

tongue: arraba

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

-

Further Reading

-

-'Oromo'. G. Gragg. In The Non-Semitic languages of Ethiopia. M. L. Bender (ed). Michigan State University (1976).

-

-'Oromo'. D. Appleyard. In The Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, 806-812. K. Brown & S. Ogilvie (eds). Elsevier (2009).

-

-A Grammar of Harar Oromo (Northeastern Ethiopia). J. Owens. Buske Verlag (1985).

-

-A Grammatical Sketch of Written Oromo. C. Griefenow-Mewis. Köppe Verlag (2001).

Oromo

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania