An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Name Origin: Swahili derives from the Arabic word sawāḥil which means "coasts".

Alternative Name: Kiswahili.

Classification: Niger-Congo, Volta-Congo, South Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Eastern Benue-Congo, Bantoid, Bantu. Based on shared characteristics and on geographical contiguity, Guthrie grouped the Bantu languages into 15 geographical (and partly genetical) zones. In Guthrie's classification Swahili belongs to Group G.

Overview. Swahili is one of the most widely spoken of the autochthonous African languages and the largest of the Bantu group. It originated in the coast and islands of East Africa but later spread inland being adopted as an international language for communication between the Indian Ocean commercial network and the Bantu interior. As a consequence, it absorbed many words and concepts from the maritime powers operating in the area, namely from Arabic, Portuguese and English as well as from other Bantu tongues. Swahili's grammar is typically Bantu, including a noun-class system and a complex agglutinating verbal morphology, but unusually for a Bantu language it lacks tones.

Distribution. The east coast of Africa, from Somalia to North Mozambique including Kenya, Tanzania and many offshore islands. Swahili is also spoken further inland, mainly as a second language, in Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. There are speaking Swahili communities outside Africa, in Western countries and in the Gulf States.

Speakers. There are around six million native Swahili speakers but many more speak it as a lingua franca. Between 50 to 100 million people in total use it as a first or second language.

Status. Swahili is an official language (along with English) in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. It is also official in the Comoros islands (north of Madagascar) where it is known as Comorian. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a form of Swahili is one of the four languages of administration. It is the only African language among the working languages of the African Union.

Varieties. Swahili has numerous dialects. In the 1930s began its standardization based on the dialect spoken in Zanzibar city. This standard is now used in publishing and education. Dialects may be grouped into geographical areas:

Somali coast

-

1.Bravanese (Chimwini) in southern Somalia, around Baraawe, between Mogadishu and Chisimayu.

-

2.Bajuni further south in Somalia up to Chisimayu.

Kenya

-

3.Pate, Siu and Amu. Three very similar dialects spoken in two islands off the northern coast of Kenya (the first two in Patta island and the latter in Lamu). Amu, written in Arabic script, is the dialect of poetry.

-

4.Mvita spoken in the island of Mombasa, the main port of Kenya.

-

5.Fundi north of Vanga in the southern Kenya coast.

-

6.Vumba spoken in Wasin Island and Jimbo near Vanga.

Northern Tanzania and offshore islands

-

7.Mtang'ata in the coast of northern Tanzania, between Pangani and Tanga.

-

8.Pemba spoken on Pemba Island.

-

9.Tumbatu in Tumbatu Island, north of Zanzibar.

-

10. Hadimu (also called Makunduchi) spoken in the southern part of the island of Zanzibar.

-

11. Unguja in central Zanzibar, especially in Zanzibar city.

Comoros Islands

-

12. Nagiza spoken in Grand Comoro.

-

13. Nzwani spoken in Anjouan.

Central and Southern Tanzania coast

-

14. Dar-es-Salaam spoken in the capital of Tanzania.

-

15. Gome in Mafia island.

-

16. Kilwa around the southern city of Kilwa.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

-

17. Ngwana.

Oldest Documents

1711-28. The oldest Swahili documents so far known are fourteen letters sent to the Portuguese of Mozambique and now in the Goa Archives in India.

1728. Utendi wa Tambuka (The History of Tambuka), an epic poem written in Arabic script.

Phonology

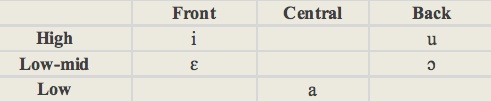

Vowels (5). Like about 60 % of all Bantu languages, Swahili has a five-vowel system:

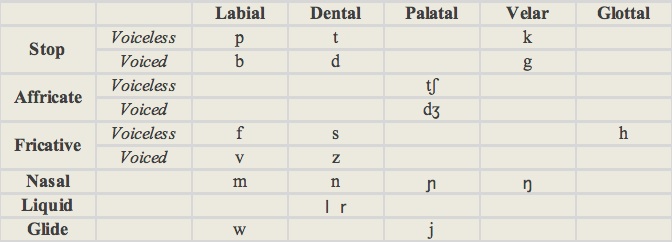

Consonants (21). The voiceless stops (p, t, k) and voiceless affricate (tʃ) are sometimes aspirated. The voiced stops (b, d, g) and voiced affricate (dʒ) might be realized as implosives (ɓ, ɗ, ɠ, ʄ, respectively). Dental (θ, ð) and velar (x, ɣ) fricatives occur in Arabic loanwords.

Tones: in contrast to most other Bantu languages, Swahili lacks tones.

Stress: falls always on the penultimate syllable.

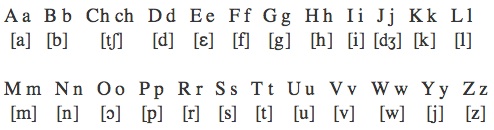

Script and Orthography.

The oldest Swahili literature was written in the Arabic script, but now a 24-letter version of the Roman alphabet is used (equivalents in the International Phonetic Alphabet are shown between brackets).

-aspiration, if it occurs, is not usually recognized in spelling.

-the implosives are not recognized in spelling.

-the palatal and velar nasals are represented by digraphs: [ɲ] by ny and [ŋ] by ng'.

Morphology

Swahili has many characteristics of an agglutinating language. Like other Bantu languages, it has a noun class system and marks morphologically the agreement between different constituents of clauses and sentences.

-

Nominal

-

•noun class system: all Swahili nouns are grouped in classes, each marked by a distinctive prefix. Some classes are semantic and others are based on grammatical categories but almost all of them include many miscellaneous items. There is no gender distinction. Proto-Bantu had nineteen classes which in Swahili have been reduced to fifteen. Classes 1 to 8 are paired, the first member of the pair is for singular nouns, the second for plural nouns. Classes 9-10 show no singular-plural contrast. Classes 11-14 have merged. Classes 12-13 have merged with 7-8. The grammatical classes 15 to 18 have no plurals.

-

Classes 1-2 for people.

-

Classes 3-4 for plants, trees, parts of the body and natural phenomena.

-

Classes 5-6 for objects that come in pairs or larger groups; augmentatives.

-

Classes 7-8 for inanimate objects, miscellanea and diminutives.

-

Classes 9-10 for animals, fruits and loanwords.

-

Class 11/14 for miscellanea and abstract qualities.

-

Class 15 for verbal infinitives.

-

Classes 16 to 18: no words, only for locatives.

-

•agreement system: it involves nominal, pronominal and verbal agreement. Adjectives, numerals, demonstratives, possessives and relatives agree with the noun by the use of affixes. Verbs agree with subject and object by the use of subject and object markers. The shape of agreement affixes is not always identical with the noun-class prefix. While the agreement morpheme is identical to the noun class prefix in the case of adjectives, other concord markers may have a different shape.

-

vi-tabu vi-le vi-zuri

-

books those beautiful

-

Those beautiful books

-

ma-chungwa ya-le ma-zuri

-

oranges those beautiful

-

Those beautiful oranges

-

•numbers: singular and plural. Plural is indicated by a prefix according to the system of noun-classes:

-

classes 1-2 : mtu (‘man’), watu (‘men’)

-

classes 3-4: mti (‘tree’), miti (‘trees’)

-

classes 5-6: jicho (‘eye’), macho (‘eyes’)

-

classes 7-8: kikapu (‘basket’), vikapu (‘baskets’)

-

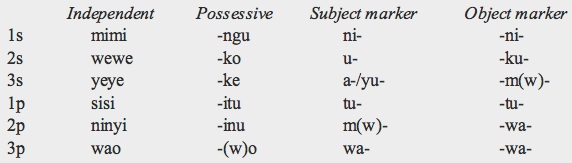

•pronouns: personal, possessive, demonstrative, interrogative, indefinite.

-

Personal pronouns may be independent, possessive, verb-subject markers and verb-object markers. Independent pronouns are optative and used mainly for emphasis. When they are employed they don't replace the subject markers in the verb complex. Possessive pronouns are prefixed by class markers.

-

Subject and object markers shown here are those of noun-classes 1 (singular) and 2 (plural) which are for humans. Other classes have different markers for the 3rd person (they don't have 1st and 2nd person markers as they include only non-human nouns). The subject and object markers not belonging to classes 1-2 are identical within each class.

-

Proximal demonstrative pronouns are based on the particle ha prefixed to the class marker; the distal ones are formed by the class markers suffixed with le. For example, wa is the prefix of class 2 (human plural) and, thus, hawa and wale mean ‘these’ (persons) and ‘those’ (persons), respectively.

-

The interrogative pronouns are nani (‘who?’) and nini (‘what?’).

-

Verbal. The minimal Swahili conjugated verb includes: subject marker-tense marker-root-mood marker. The verb complex may also include negative, relative, object, and plural markers as well as derivational affixes. The markers and verb root follow a precise order filling up to ten possible slots which are not all of them occupied at the same time:

-

1. pre-initial negative marker

-

2. subject marker (SM)

-

3. post-initial negative marker

-

4. tense marker

-

5. relative marker

-

6. object marker (OM)

-

7. root

-

8. derivational affixes

-

9. final (indicating mood)

-

10. post-final (indicating plural)

-

•The negative marker can precede or follow the subject marker (positions 1 and 3 are mutually exclusive).

-

•The subject marker indicates the class, person and number of the subject and is obligatory except in the imperative.

-

•The tense markers are na/a (present), li (past), me (perfect), ta (future), ka (consecutive), ki (continuous), nge/ngali (conditional). Negative conjugations have a different set of tense markers. The tense marker is obligatory except in the imperative and the subjunctive.

-

•The relative marker is used to build a relative clause and agrees with the class of the subject noun/pronoun.

-

•The object marker indicates the class, person and number of the object; it is used mainly for humans.

-

•The root can be extended with a number of derivational suffixes conveying passive, causative, applicative, separative, reciprocal, stative and other meanings; more than one extension can be used.

-

•The final is always the vowel a, except in the negative present indicative where it is i, and in the subjunctive where it is e.

-

•The post-final is a plural marker (ini/ni) that only occurs in the 2nd person plural imperative and in the verbal forms with the object marker wa to differentiate the 2nd person plural from the 3rd plural (otherwise identical).

-

Examples of Swahili conjugations:

-

ni-ta-wa-omb-e-ni

-

SM1s-FUT-OM2p/3p-ask-FIN-PF (slots: 2-4-6-7-9-10)

-

I'll ask you (all)

-

The post-final ini differentiates the 2nd person plural OM from the 3rd person plural OM that have otherwise identical markers (wa). The final a of the indicative becomes e in contact with ini.

-

vi-kombe vi-wili vi-li-vunj-ik-a

-

cups two SM3p-PAST-break-STAT-FIN (slots: 2-4-7-8-9)

-

Two cups were broken.

-

'Cups' belongs to class 8 (inanimate plural) whose prefix is vi. The numeral and subject marker carry the same prefix. Position 8 is filled by an stative extension (ik) that denotes a state or condition.

-

ha-li-sahau-lik-i

-

NEG-SM3s-forget-STAT-FIN (slots: 1-2-7-8-9)

-

It is unforgettable.

-

The SM is that of class 5 (li). Position 9 is filled by an stative extension. The final i corresponds to the negative indicative.

-

u-si-mw-amb-i-e

-

SM2s-NEG-OM3s-tell-APP-FIN (slots: 2-3-6-7-8-9)

-

Don't tell him/her.

-

The subjunctive mood may be used to express commands, like in this sentence. In the subjunctive the negative marker follows the SM and a tense marker is not required. The subject and object markers are those of class 1 (human, singular). The extension in position 8 is an applicative to indicate to whom the action applies; it supplies the role of English prepositions. The final e corresponds to the subjunctive.

-

wa-na-o-kuj-a

-

SM3p-PRES-REL-come-FIN (slots: 2-4-5-7-9)

-

They who come.

-

The subject and relative markers are those of class 2 (human, plural).

-

yu-le m-tu m-moja m-refu a-li-ye-ki-som-a ki-le ki-tabu ki-refu

-

that person one tall who read that book long

-

That one tall person who read that long book.

-

M-tu is a class 1 noun (human, singular) and all its modifiers (demonstrative yu-le, numeral m-moja, adjective m-refu) carry the class 1 concord prefix (notwithstanding that the shape of the demonstrative one is different). Ki-tabu is a class 7 noun (inanimate object, singular) and its modifiers (demonstrative ki-le and adjective ki-refu) carry the class 7 concord prefix. The verb complex has six elements: SM a corresponding to class 1, 3rd person singular; past marker li; relative marker ye corresponding to class 1; OM that carries the concord marker ki for class 7; root som, and indicative marker a.

-

The imperative has only 2nd person forms, the singular is identical to the root plus a, the plural adds the post-final marker:

-

you ask: omba

-

you (all) ask: ombeni

-

The infinitive is made by joining the prefix ku of class 15 to the root followed by the mood vowel (e.g. kuomba).

-

Syntax

The basic order in the Swahili sentence is Subject-Verb-Object-Adjunct. However, word order is comparatively free and a topicalized item might be moved to front position. The noun-phrase is head-initial i.e. the head-noun is placed first and its modifiers (adjectives, demonstratives, etc) follow it. However, demonstratives may be placed before the noun to stress definiteness. There is just one, all purpose, preposition (na), but the verbal applicative extension supplies the role of most prepositions and, besides, verbs and nouns may function as such.

Lexicon

Swahili has borrowed a great deal from Arabic and around 35 % of its vocabulary derives from it. To a lesser extent from Portuguese (mainly in the sixteenth century), Persian, Hindi and several Bantu languages. Lately, English has become the major source of loanwords.

Basic Vocabulary

The numerals for 6, 7, 9 and the multiples of 10 (including 100) derive from Arabic.

one: moja

two: mbili

three: tatu

four: nne

five: tano

six: sita

seven: saba

eight: nane

nine: tisa

ten: kumi

hundred: mia

father: baba

mother: mama

brother: kaka, ndugu

sister: dada, ndugu

son: mwana, bin (from Arabic)

daughter: mwana, binti (from Arabic)

head: kichwa

face: uso

eye: jicho

hand: mkono

foot: mguu

heart: moyo

tongue: ulimi

Key Literary Works (forthcoming)

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

-

Further Reading

-

-'Swahili and The Bantu Languages'. B. Wald. In The World's Major Languages, 883-902. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-'Swahili'. L. Marten. In Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, 1026-1030. K. Brown & S. Ogilvie (eds). Elsevier (2009).

-

-Swahili Grammar (Including Intonation). E. O. Ashton. Longman (1944).

-

-Swahili Language Handbook. E. C. Polomé. Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington DC (1967).

-

-Swahili: The Rise of a National Language. W. H. Whiteley. Methuen (1969).

Swahili

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania